By Celeste Hawkins

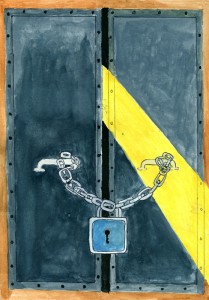

Australia is the only country in the world where there is no end date for refugee detainees.

Pause and think about that for a moment.

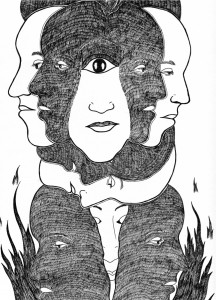

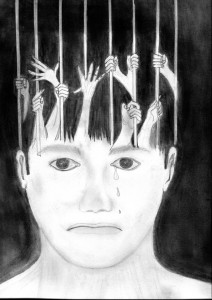

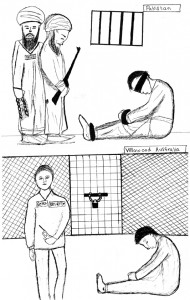

One can only imagine the traumatic experience these individuals have faced in their country of origin. Added to that, the heightened stress in boarding an unknown vessel and sailing in perilous conditions. Then finally, to arrive in a ‘processing centre’ or ‘detention centre’; where they are left with no certainty and locked away with no end in sight. There have been numerous reports in the media of the degrading conditions that these detainees must endure whilst in these places. The news of our treatment of asylum seekers has also been made known to the International Community and Human Rights organisations. Thankfully, some detainees have had the opportunity to express their feelings and emotional states through their art making; using whatever means they can find to do so.

“Art can do lots of things. It is a vehicle for self development, for personal expression and for the creation of inner worlds.”

These are the carefully chosen words of Safdar Ahmed, founder of the Refugee Art Project. Set up by a collective of Artists and fellow Academics, the project is now in its fourth year. Safdar kindly updated me on the work that has been occurring with the project and a bit of background as to how and why he got it started.

What is your own personal experience or reason for being concerned about the plight of asylum seekers?

I have no personal experience of exile, although my family on dad’s side are Indian Muslims who are discriminated against in their own country, so in that context I feel some empathy for scapegoated and marginalised minorities. The bulk of my concern about the plight of asylum seekers stems from not wanting to see our government indulge in abusive and sadistic policies that are explicitly designed to punish refugees and destroy their lives.

You have a Bachelor of Fine Arts and are a University Lecturer. In your Ted talk you discuss art as being your ‘refuge’, especially as a teen. Was this the catalyst to get this project happening?

I think my own experiences of depression and recovery have led me to believe that art can help people to express their difficulties and perhaps even understand them. On a less personal note, a catalyst behind the formation of Refugee Art Project is that many asylum seekers and refugees (particularly those whose cases are in process) do not have a public voice. If they are in detention they are directly censored and kept hidden from the media. If they live in community detention they are often too afraid to express themselves politically in case the Department of Immigration punishes them for it and throws them back into detention. In this context, it seems important to facilitate the art and self-expression of asylum seekers and refugees, which is what our organisation aims to do.

Can you recall the particular moment or time when you thought about creating the zine project? Did it occur much longer after the art workshops?

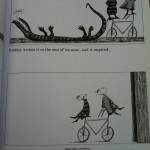

Because zines have always been a way for underground communities to define themselves, and to produce their own culture and media—away from hegemonic political and social discourses—they seemed the best format in which to present the amazing artworks that refugees in detention were making. I think the idea for making the zines arose in response to the amazing quantity of black and white drawings refugees produced, which were too delicate and large in number to exhibit. By presenting their art, writing, poetry and occasional interviews, the zines are able to both validate the diverse voices of refugees and to hopefully convey those voices to the Australian public.

What was the initial reaction of the refugee community both inside and outside Villawood?

The reaction amongst refugees towards our zines has been very positive. Even people in detention who aren’t directly involved in our project have read them with interest and discussed them, which is nice to see.

What has been your reaction from the Australian Community?

The reaction from ordinary Australians has been interesting. I think for many readers the zines present an opportunity to hear directly from refugees, which most have never experienced. They also force the reader to see refugees in a new way—as complex human beings who cannot be viewed only through the prism of their persecution and suffering, which is how they are commonly represented in the media and amongst refugee advocates. Hopefully our zines give people a small insight into the former lives, hopes, aspirations, humour, whimsy, sadness, and just the daunting scope of intense, complex and messy emotions that refugees in and out of detention experience.

How about the International Community?

So far there’s been a strong interest from refugee support organisations and zine distributors and libraries in places like the Netherlands, Germany, the US and elsewhere. It’s heartening to create solidarity with other refugee rights organisations and the zines no doubt play a role in showing what the situation of asylum seekers in Australia is like.

Can you discuss one particular case study or individual where they have clearly benefited from their art-making journey?

We have a few zines that contain the work of individuals including a beautiful issue by Murtaza Ali Jafari. Murtaza is a Hazara refugee from Afghanistan who we have known and built a solid friendship with over many years. The zine shows his earliest drawings, which he made in the Villawood detention centre, where he was locked up for over two years. It charts his artistic growth, as his style became progressively more graphic and intense. He says in the zine that art helped him cope with the stress of living in detention and gave him something to feel proud of. His work no doubt refracts the difficulties he experienced at Villawood, but overall I think it’s an amazing testament to his courage and strength.

You are not for profit organisation. Apart from the sales of artworks, where do you obtain the majority of your funding? What areas have the profits of sales been most helpful?

Because we are a not for profit organisation, we rely for our survival on donations, the occasional support of ethical institutions and the generosity of galleries who will not charge a commission on our shows. We are lucky to have a studio in north Parramatta which is made available through PopUp Parramatta and Parramatta council. From the sale of refugee artworks in our exhibitions, all proceeds go straight back to the refugee artists, to support themselves and their families. We’ve organised a few fundraising events to pay for art materials and to keep our classes going, although the zines are not a fundraising instrument. Because we want them to be affordable, our zines pay back their own printing and distribution and that’s about it.

You said during your Ted Talk that after the first exhibition turn out in 2011, that it had ‘built a bridge between the people in detention and people in the community’. Has that bridge become stronger over time?

Yes I hope so. I think our exhibitions have fostered greater connections between refugees in detention and people in the general community. Certainly our art workshops in Parramatta have helped to smooth the transition of refugees into the community once they are released from detention. In our workshops, exhibitions and other public events we aim to facilitate the empowerment, belonging and social inclusion of refugees.

How have the sales been for the zines? Which social platform have you found most successful for getting them out to the public?

We’ve been able to sell our zines through the lovely people at the Take care zine distro here in Sydney and the Sticky Institute in Melbourne. Facebook and Twitter have been the best networking platforms for promoting our zines, and our project more generally.

How is the new documentary coming along?

The Thomas project is very exciting! We are putting the finishing touches on a short interview documentary that was directed and produced by the talented filmmaker, Agnieszka Switala. Thomas Wales is a traditional landowner and spokesperson for the Thanakwith people in Far North Queensland. He worked as a service provider in the remote Sherger detention centre, where he developed a strong compassion and empathy for refugees. I think it’s rare to hear the insights of a first Australian who has experience of working and consolidating relationships with refugees in detention. He also relates the demonisation of refugees in Australian society with the marginalisation and discrimination that indigenous people face in this country, so his perspective is very interesting on that point.

What is the best way for people to help?

People can help us by making a financial donation to our organisation, which helps to pay for art materials and keep our workshops going. I think the zines are an excellent educational resource so it’s also a good idea to pitch them as worthy purchases for your local school or library.