By Celeste Hawkins

Clare Mc Cracken calls her self a mixed media artist, but most of her art is ever-present in the streets of various communities, so many describe her as a public artist. Often placing thought provoking artworks right in the public eye, (and many times in unlikely places); it seems a perfect vocation for Clare who is passionate about the interaction, reactions and discussion that these public art works generate.

Tell me about your background, how did you spend your childhood?

I grew up on one hundred acres of bush in North East Victoria. My parents built a house out of recycled bridge timber and SEC poles. All our cooking was done on a slow combustion stove, even in the middle of summer, so the first eighteen years of my life were spent collecting wood, climbing trees and building cubbies. For most of my childhood we didn’t have a television so books, stories and board games were the things that we did as a family in the evenings. While no television has meant that I miss quite a few popular culture jokes and embarrassingly often sob and get scared at the movies (as I was never desensitized) listening to my parents stories about their childhood and our extended family taught me all of the life skills that children get from well written television shows. However, the best thing about oral story telling is that you visually get to unleash your imagination. With no available images the characters and their landscape can look however you want them to look!

‘Throne’ Installed in Federation Square, 2009

What got you started?

I moved to Melbourne after high school to do an undergraduate in Creative Arts at Melbourne University. After 18 years in the bush, and country towns, I was really excited about the city. Creative Arts was a great degree that allowed students to major in Theatre Studies, Media Studies, Visual Arts or Creative Writing. It also combined rigorous theory with creative, hands-on practice. After experimenting with all of the areas I ended up majoring in Visual Arts with a sub major in Theatre Studies. In my honors year I wrote about the Situationist International, who created site-specific public art works post the Second World War as a way of protesting against the redevelopment and increased privatization of European cities.

I was also very aware that many of the highly intelligent and generous people I grew up with found the formal setting of the art gallery with its white walls and strict rules both alienating and intimidating. Public art gave me the opportunity to make art that communicated with these people, it also allowed me to enter into a discourse about the places that we live in and experience every day. I started to see that art had the power to help people reconnect with their public space and local milieu. Interestingly, I had always thought that I would be a critic discussing these issues, until I was commissioned by the City of Greater Dandenong to make a work while I was doing my Masters at RMIT in Art in Public Spaces. I loved that process so much that I completely changed direction, and while theory remains a very important part of my practice, I became an artist.

‘Neighbourhood Watch’ Storey projection 2010 and 2012

What are some of your most popular installations or murals and why?

I think one of my favorite public art works is Rachel Whiteread’s House (now demolished). House was a concrete cast of an entire Victorian terrace house in East London. Whiteread regularly casts the negative spaces of objects, highlighting ideas of memory and loss. For me House is one of her most powerful works because of the site that it is located on. It was the last of hundreds of Victorian terrace houses to be demolished in the area to make way for a high-rise development. Because the houses were public houses, the people in them had no autonomy over their destruction. Many of the families had lived in them for years and they saw them as their family home and, while moving from them to a high-rise may have meant more modern living conditions, they were losing places that were filled with history and memories – they were loosing a life style. Whiteread’s impenetrable House was a monument to these disenfranchised people who had little opportunity to be heard. It was an acknowledgement of their grief.

A little closer to home, I think Martine Corompt & Philip Brophy’s work No Answer is also a very memorable work. Installed in Lush Lane in 2006 for around six months, the work was commissioned by Melbourne City Council as part of their Laneway Commissions. The work was comprised of eight public phones that were mounted on the wall at the end of the laneway, above the height of a person. Throughout the night and day the phones would ring, however their height made them unanswerable. When the work was installed, Telstra was pulling out most of their public phones. While this move did not affect those of us that could afford a mobile phone, it seriously affected those that could not afford one (or a landline for that matter). No Answer poetically highlighted this issue.

Why is Public Art so important?

I think the aforementioned examples really highlight how public art can be used to give public issues a public voice, and to help people deal with the changing environments that they once truly connected with. Naturally it also has the effect of rejuvenating locations (which was the whole concept behind Melbourne City Council’s Laneway Commissions). There is also a lot to be said for simply filling people’s lives with the unexpected – giving them the opportunity to smile or unleash their imagination.

‘Speed Check’ Permanent work installed Oakwood Park, Noble park 2008

What sort of people do you work with?

One of the most rewarding elements of my job is the diversity of people I get to work with. Basically, I hope I have the opportunity to work with all sections of the community but at this point I have probably engaged more thoroughly with young people (particularly at risk young people) and communities affected by large scale infrastructure projects. One of my favorite projects thus far involved the hotrod and car enthusiast community around the Knox area. I’d love to work with them again!

Tell me about some of the reactions from the public:

One of the great challenges of public art is gauging the way that it is interacted with and reacted to. Unfortunately, I think we are all far more likely to write a letter of complaint when we don’t like something. Having said that, occasionally, after installing a work, a really generous member of the public will leave a message on my website.

Most of the feedback I get is during an install – when I’m working on site. A couple of years ago I spent two weeks painting a mural in a breezeway that led to a public toilet in Dandenong. Because I was there so long, I had regular conversations with the community. The most rewarding part of this process was hearing people’s initial concerns about the location and my design, and how they evolved overtime as it was completed. On my final day, people would say things like:

“I used to feel unsafe here so I thought this thing was a waste of money but it really improves this site.”

“When I first saw the colours you had chosen I didn’t want to tell you but I thought they were terrible. Now they are all on the wall they look great – I guess that’s why I’m not an artist.”

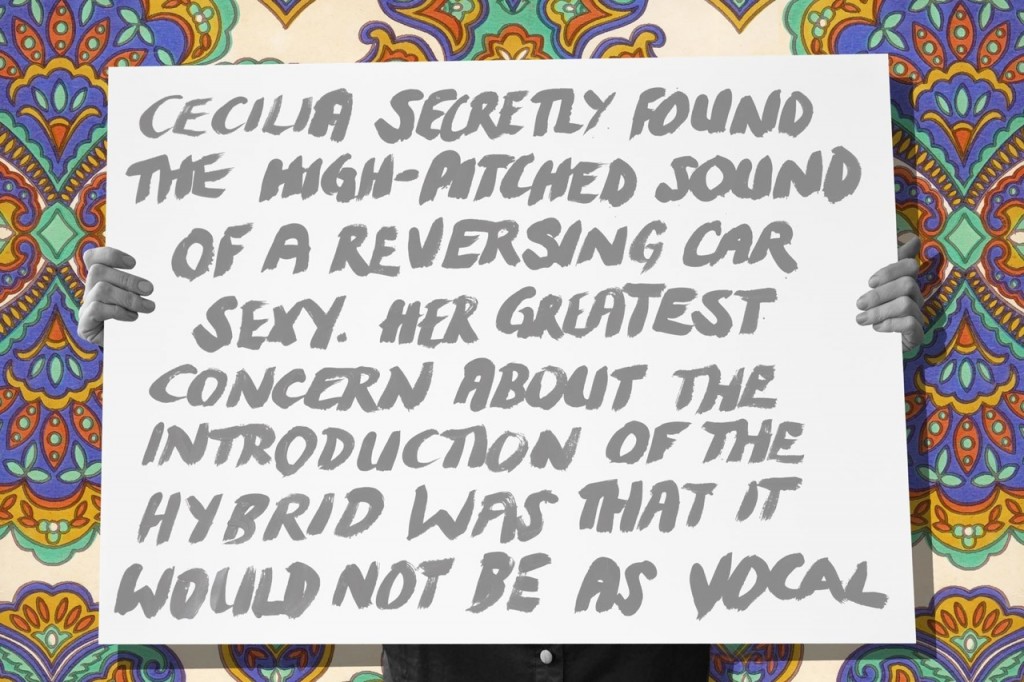

‘Cecilia Secretly’-Digital Print 2010

Reactions from collaborators:

I think the thing that frustrates me the most is commissioning bodies that underestimate their public – who choose not to commission interactive and contemporary works because they believe that their public will not understand. The more you work in the public realm, the more you realize just how intelligent and intrepid communities are. If you take people on the journey with you, and include them from the very beginning, there is nothing stopping you from installing innovative, contemporary works anywhere. I think my favorite reaction from collaborators is when they are surprised by their community’s positive reaction to work.

How many years have you been working and how has it changed?

I finished my Masters and started practicing full time four years ago so little has changed in my time. For many more established artists, the big change would be commissioning bodies’ shift from long-term permanent works to ephemeral works. Overwhelmingly, I think this shift has been really positive because it has allowed artists to take risks and has meant that artists, other than sculptors, have been able to work outside the gallery.

From where does the funding come?

Almost all of my funding comes from local government. However, I have also been commissioned by body corporates of large buildings and by private organizations like Federation Square. I have also occasionally self-funded projects that I really want to do.

Are governments, councils and fundraising groups eager to fund public art projects?

Melbourne has some really innovative and generous local governments that have sound public art budgets and pioneering commissioning practices. Melbourne City Council and the City of Greater Dandenong are two that I regularly work with. Knox City Council has some really innovative and large-scale youth programs that they run, such as their Knox Festival Artist in Schools program. They also have two public art platforms that they use to display the works of their community.

Do you have any advice for young artists or anyone wanting to contribute?

If you are interested in getting involved within your own community, contact the Cultural Services Coordinator or Place Maker within your local government. In my experiences, local government loves to know who in their community is interested in being involved, and they are very good at finding ways to involve enthusiastic locals.